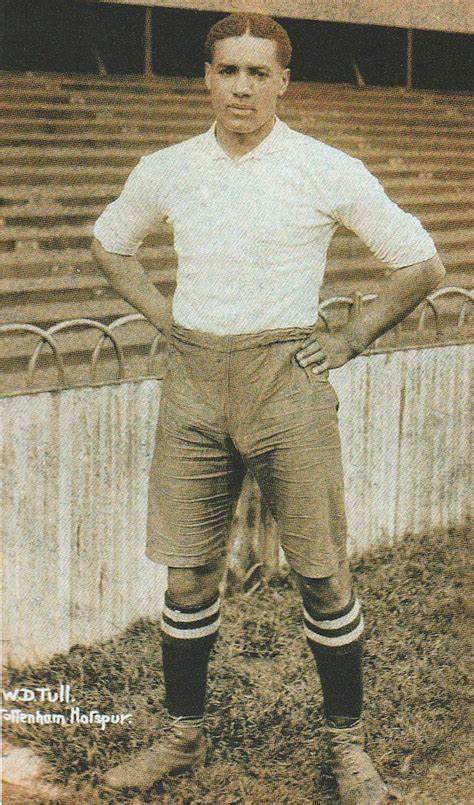

Walter Tull (28 April 1888 – 25 March 1918) was one of the first black professional footballers before the Great War. Walter’s father had arrived from Barbados in 1876 and married a girl from Folkestone. Walter was serving an apprenticeship as a printer when he was signed for Tottenham Hotspur. He played only a few games; in a game at Bristol City in 1909 he was racially abused by fans in what the Football Star called ‘language lower than Billingsgate’ He was subsequently sold to Northampton Town where he flourished under the guidance of legendary manager Herbert Chapman, making 110 first team appears for the club. At the outbreak of war in August 1914 Walter, then the subject of transfer negotiations between Northampton and Glasgow Rangers, joined the 1st Football Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment. The Army soon recognised Tull's leadership qualities and he was promoted to the rank of sergeant. In July 1916, he took part in the major Somme offensive. He survived this experience, but in December 1916 he developed trench fever and was sent home to England to recover. Tull had impressed his senior officers and recommended that he should be considered for further promotion. When he recovered from his illness, instead of being sent back to France, he went to the officer training school at Gailes in Scotland. Club records show that, in February 1917, he signed to play for Rangers after the war. Despite military regulations forbidding "any negro or person of colour" being an officer, Tull received his commission in May, 1917. He was then sent to the Italian front where he led his men at the Battle of Piave with such distinction that he was mentioned in dispatches for his "gallantry and coolness" under fire. Tull stayed in Italy until 1918 when he was transferred to France to take part in the attempt to break through the German lines on the Western Front. On 25th March, 1918, he was ordered to lead his men on an attack on the German trenches at Favreuil. Soon after leaving the trenches, Tull was hit by a German bullet. He was such a popular officer that several of his men made valiant efforts under heavy fire from German machine-guns to bring him back to the British trenches. He died in No-Man's-Land soon after being hit - his body was never found. His commanding officer wrote to Walter’s brother, ‘He was popular throughout the battalion. He was brave and conscientious. The battalion and company had lost a faithful officer, and personally I have lost a friend’.

Walter Tull